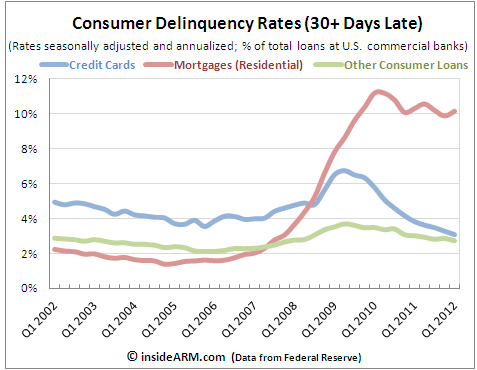

Consumer debt delinquencies in the U.S. have been steadily falling since 2010. Late payment rates on auto loans and credit cards are now near record lows. But the two loan types with the largest outstanding balances – mortgages and student loans – have seen delinquencies stuck at maddeningly high rates, with the possibility of further increases.

The Federal Reserve said last week in its quarterly report on loans from commercial banks that the aggregate 30+ day delinquency rate for credit card accounts among its member banks was 3.07 percent in the first quarter of 2012, the lowest reading of the figure since the Fed started tracking it in 1991.

Likewise, credit reporting agency TransUnion reported Wednesday that the national auto loan delinquency rate for the first quarter reached its lowest level since TransUnion began tracking the data in 1999. TransUnion tracks auto loans that are 60+ days past due.

But the Fed’s report last week also noted that residential mortgage delinquencies increased to 10.18 percent in the first quarter, while late payments on all other consumer loans decreased slightly.

The increase in residential mortgage delinquencies was hardly a shock. Since early 2011, the mortgage delinquency rate has been flat overall, oscillating slightly up and down quarter to quarter and hovering around the 10 percent mark. Other loan types have been moving steadily lower.

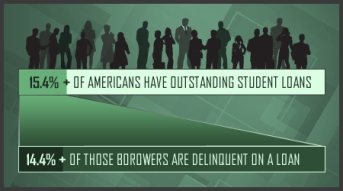

And then there’s student loans. Because commercial banks hold a small minority of delinquent student loans on their books, the overall delinquency picture for college lending is not reflected in the Fed’s quarterly report.

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York, separately from the national Fed office, recently conducted an exhaustive study of the student loan debt market. Using data from the third quarter of 2011, the report said that the delinquency rate among all student loans was roughly 10 percent, with 14.4 percent of all education borrowers delinquent on at least one student loan. And the delinquency rate is growing.

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York, separately from the national Fed office, recently conducted an exhaustive study of the student loan debt market. Using data from the third quarter of 2011, the report said that the delinquency rate among all student loans was roughly 10 percent, with 14.4 percent of all education borrowers delinquent on at least one student loan. And the delinquency rate is growing.

The difference in delinquency rates among loan types with low rates (auto and credit card, for example) and those with high rates (mortgages and student loans) is probably explained by minimum payment levels. Mortgages and student loans typically require much higher monthly payments than credit cards and auto loans. Consumers, still beset by persistently high unemployment, are finding it easier to pay a few hundred dollars per month to keep their car or prevent their credit cards from going into default than to pay the thousand dollars or more required to stay current on home loans and student loans.

The difference in delinquency rates among loan types with low rates (auto and credit card, for example) and those with high rates (mortgages and student loans) is probably explained by minimum payment levels. Mortgages and student loans typically require much higher monthly payments than credit cards and auto loans. Consumers, still beset by persistently high unemployment, are finding it easier to pay a few hundred dollars per month to keep their car or prevent their credit cards from going into default than to pay the thousand dollars or more required to stay current on home loans and student loans.

The ARM industry should pay very close attention to the escalating delinquency rates in the two largest consumer credit markets. Not only does it present an opportunity for collection work, it speaks to the concept of “wallet share” that many debt collectors encounter in their communications with debtors, regardless of what type of debt they are attempting to collect.

![[Image by creator from ]](/media/images/patrick-lunsford.2e16d0ba.fill-500x500.jpg)

![Report cover reads One Conversation Multiple Channels AI-powered Multichannel Outreach from Skit.ai [Image by creator from ]](/media/images/Skit.ai_Landing_Page__Whitepaper_.max-80x80.png)

![Report cover reads Bad Debt Rising New ebook Finvi [Image by creator from ]](/media/images/Finvi_Bad_Debt_Rising_WP.max-80x80.png)

![Report cover reads Seizing the Opportunity in Uncertain Times: The Third-Party Collections Industry in 2023 by TransUnion, prepared by datos insights [Image by creator from ]](/media/images/TU_Survey_Report_12-23_Cover.max-80x80.png)

![[Image by creator from ]](/media/images/Skit_Banner_.max-80x80.jpg)

![Whitepaper cover reads: Navigating Collections Licensing: How to Reduce Financial, Legal, and Regulatory Exposure w/ Cornerstone company logo [Image by creator from ]](/media/images/Navigating_Collections_Licensing_How_to_Reduce.max-80x80.png)

![Whitepaper cover text reads: A New Kind of Collections Strategy: Empowering Lenders Amid a Shifting Economic Landscape [Image by creator from ]](/media/images/January_White_Paper_Cover_7-23.max-80x80.png)